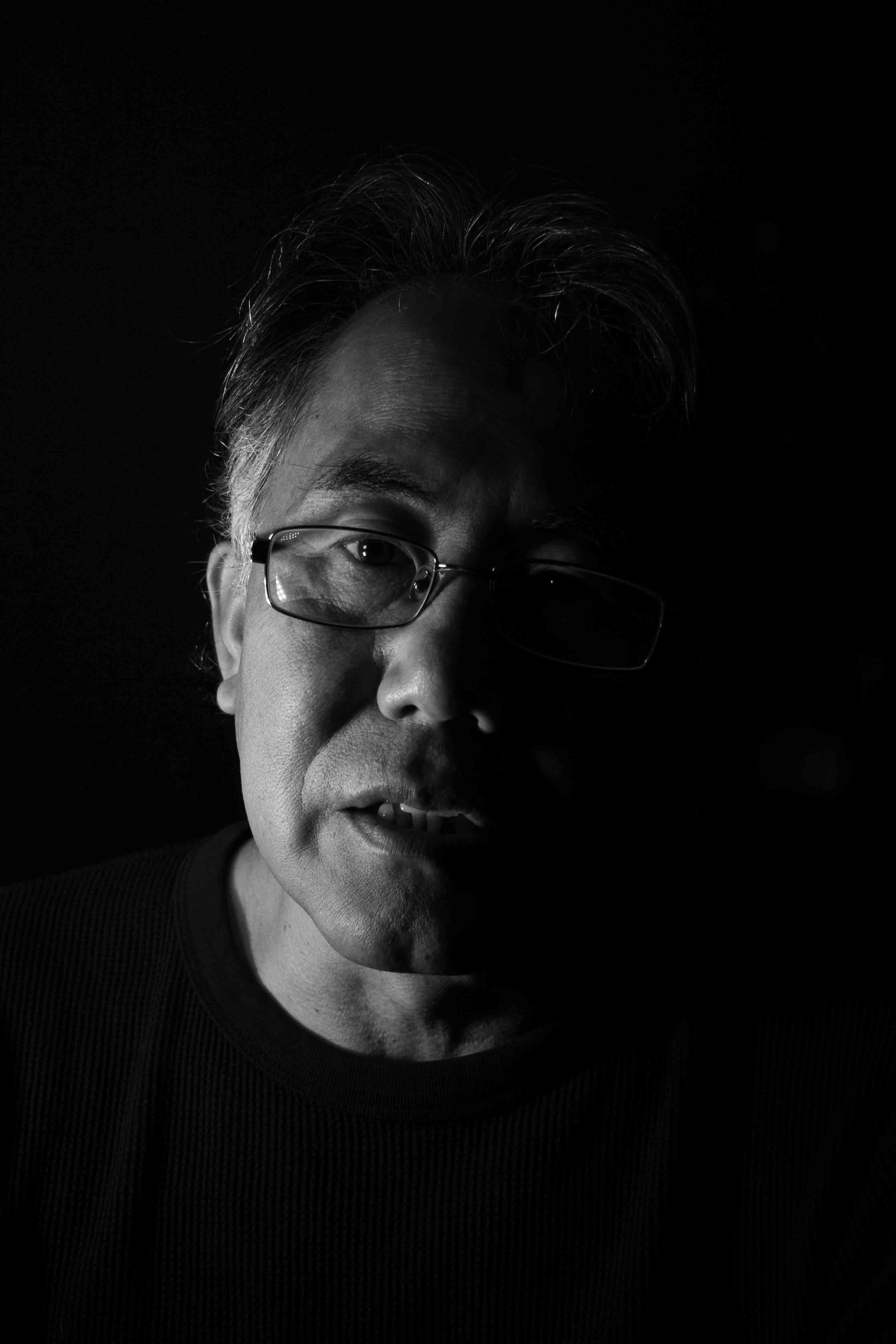

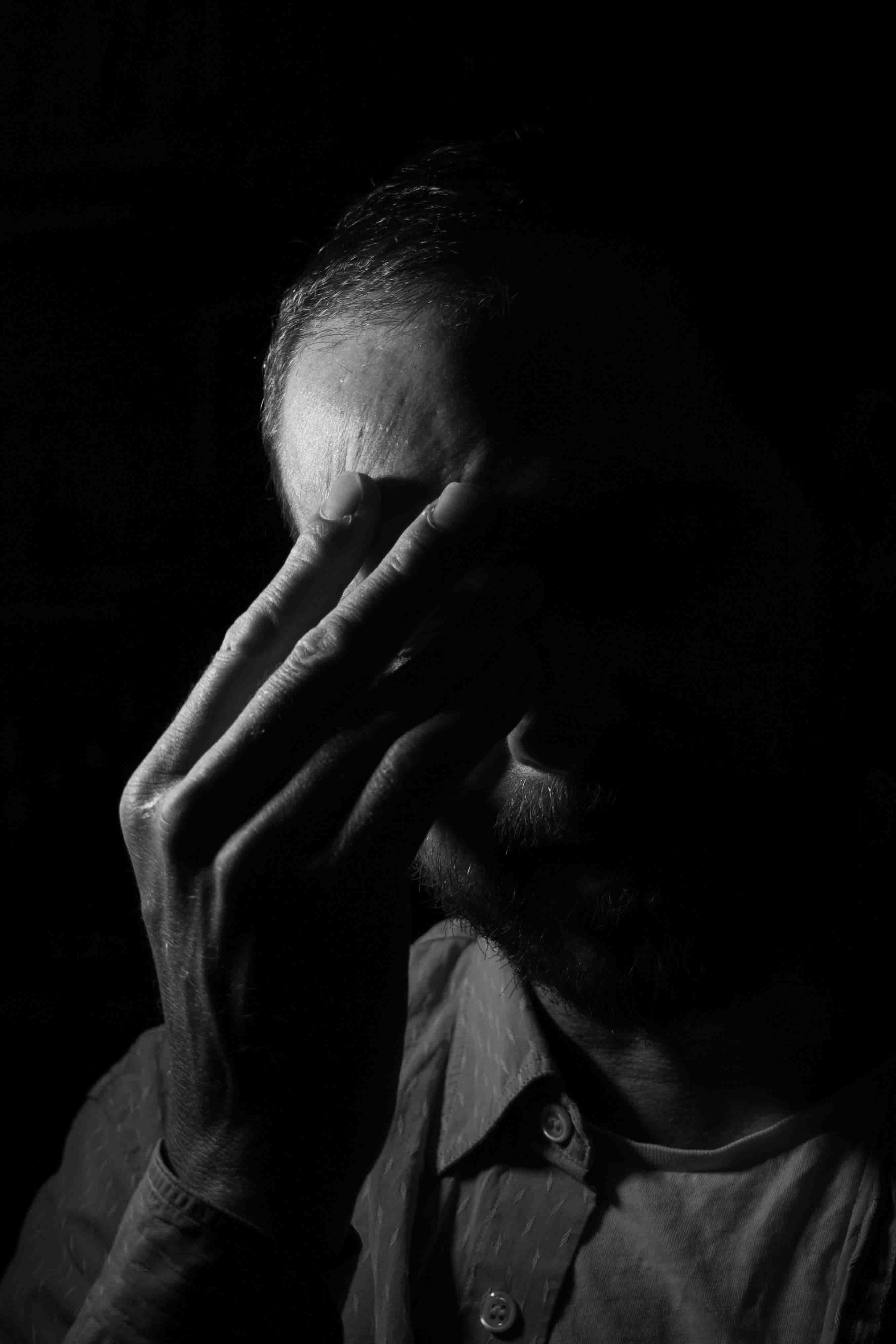

Charlie is a conservation scientist, writer and environmental activist working with societal responses to environmental crises.

I ask him if he feels hope, “Yes and no – I feel more hope than I’ve ever felt before, thanks to the rise of activism. Yes, the problems are so much worse – but we’re much closer to change now. The only hope we have is people power – either we take our planet back or we lose it.” He continues, “but I don’t like the idea of hope – hope is related to faith, it’s magical – somehow it will be ok. For a lot of people hope can be disempowering – ‘it will be OK, so I don’t need to fight’. But I don’t need hope to fight. I understand that hope is motivational and empowering on an individual level, but on a societal level, hope is really dangerous.”